Auburn Friends

Some wonderfully encouraging biographies and an occasional brief exhortation or word of wisdom for our friends who meet together in Auburn and for anyone else who would like to listen in. Our desire is only to grow in grace and in the knowledge of the Lord Jesus Christ, for His glory.

Auburn Friends

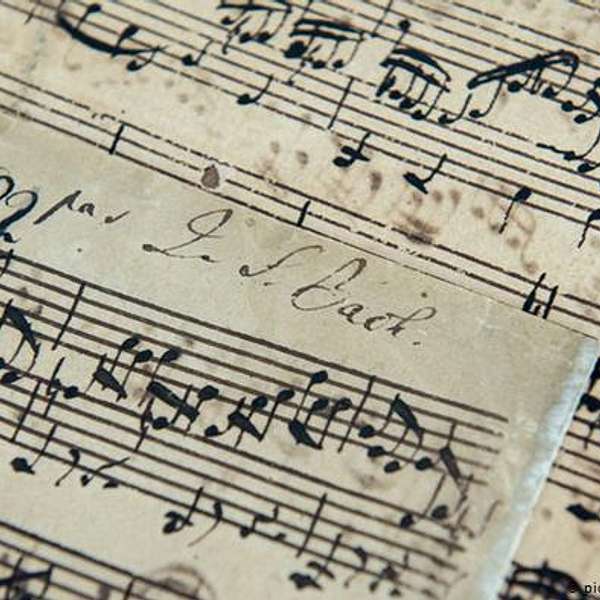

Worship and Authenticity

Concerning the Chaconne (from Bach’s Partita No. 2 in D Minor): “On one stave, for a small instrument, the man writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings. If I imagined that I could have created, even conceived the piece, I am quite certain that the excess of excitement and earth-shattering experience would have driven me out of my mind. If one doesn’t have the greatest violinist around, then it is well the most beautiful pleasure to simply listen to its sound in one’s mind.” — Romantic composer Johannes Brahms in a letter to fellow composer Clara Schumann.

...

That, I submit, is the worship woven with love and beauty that made Bach’s work ultimately authentic.

On the Chaconne from Bach’s Partita No. 2 in D Minor.

Concerning the Chaconne: “On one stave, for a small instrument, the man writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings. If I imagined that I could have created, even conceived the piece, I am quite certain that the excess of excitement and earth-shattering experience would have driven me out of my mind. If one doesn’t have the greatest violinist around, then it is well the most beautiful pleasure to simply listen to its sound in one’s mind.” — Romantic composer Johannes Brahms in a letter to fellow composer Clara Schumann.

The first quote is written by a man for whom personal emotions and feelings were of the utmost importance, a composer from the Romantic period. In it, he stresses deep thoughts and powerful feelings. The story, backed by a controversial theory put forward by some music historians, goes that Bach wrote the Chaconne after returning home from a journey to discover that his first wife and the mother of seven of his children, Maria Barbara, had died. In this understanding, Bach has written his personal grief into this piece, which is then shared by all who hear. But the apparent ‘problem’ with this theory, is that “there is no evidence that Bach himself considered the Chaconne to encode an entire vista of the universe or to sound out his own emotional depths. Such Romantic notions would never have occurred to a court composer who had trained in the late 1600s as a Lutheran town organist. Creating art then and there was not an act of personal expression but one of civic or religious service. Of course emotions could be depicted and messages delivered. But musicians of Bach’s generation did not need to feel an emotion in order to depict it. It was the next generation, beginning with Bach’s own son Carl Philipp Emanuel, who began to demand that a musician express emotions in a way we would call ‘authentic’.“ (Michael Markham in the LA Review of Books.)

The implication in this pushback (whether or not Markham intended it) seems to be as follows: If Bach wrote his personal grief into the Chaconne, then Bach wrote with authenticity and personal expression. But Bach came from a time where musicians did not write with authenticity and personal expression, but for civic or religious service (duty and worship). Therefore, Bach could not have written his personal grief into the Chaconne because he did not write with authenticity and personal expression because he wrote for civic or religious service. What caught my attention within this implication was the implicit dichotomy that if one does something in and for duty and worship, then one is not doing it with authenticity and personal expression. Whether or not my comments are true about this specific instance of certain persons’ interpretation of Bach is besides the point. What is true is that people today often live with this perspective and mentality.

“The Chaconne was divided into three large sections. The dark and brooding outer sections flanked a hymnlike inner one that evoked peace, gratitude, and optimism. Was it far-fetched to think that Bach, a devout Christian, might have offered the Chaconne as an expression of the Holy Trinity, its bedrock spiritual principle? The first section, in D minor, would represent the Father; the next, in D major, the Son; and the final section, in D minor, the Holy Spirit. This line of thought intrigued me, even though I was on shaky footing as a secular Jew with only the flimsiest knowledge of Christianity. The more I looked, however, the more ‘threes‘ I found. The Chaconne’s basic building block was a three-beat bar, the initial theme appeared three times — at the beginning, the middle, and the end — and then there were those evocative three-note groups that appeared over and over again. Was the Chaconne some kind of message in a bottle destined for (dare I think it?) God?” — An excerpt from Violin Dreams by violinist Arnold Steinhardt.

The second quote is by a man who dares to think that perhaps Bach wrote the Chaconne as worship to God. But if the Chaconne is worship to God, then is it true that it is no longer authentic? It depends on the working definition of what it means to be authentic. Doubtless countless essays, theses, and blog posts have been written on this topic and no shortage of ink, physical or otherwise, proverbially spilled over disagreements concerning it. It seems to me that what is often mistaken to be ‘authenticity’ is actually and more precisely ‘self-centred self-expression’. By self-centred, I don’t mean the usual meaning of selfish or greedy, but rather the literal sense of the self being in the centre, of the ‘I’ being of the highest importance, and of my world being about me (egocentrism). Hence, self-centred self-expression means acting in individualistic ways that are self-defined and self-focussed. It is the freedom to love myself and to put myself first because I deserve it. It is living for myself. Indeed, this attitude is celebrated by today’s culture and vaunted in our society. If we use this mis-definition, then it is indeed true that worship and authenticity are at odds. For worship means being other-centred and other-defined.

But if authenticity means living from the desire to know as we are known, if authenticity means loving because He first loved us, if authenticity means having the peace that surpasses all understanding as broken and hurting people in a broken and hurting world, if authenticity means being compelled not by our unrestrained passions but by the love of Christ — having the liberty to live as we ought, if authenticity means being human in the truest and deepest way — the way God made us and intended us to be, the way for which God sent his own Son to die, the way in which the truest human to have ever human-ed human-ed, if authenticity means the Imago Dei, the Image of God, then worship and authenticity are not at odds at all. In fact, worship is only true when we are authentic and we are only truly authentic when we live in worship.

There are two stories associated to Bach’s deathbed. His last words were to his second wife, Anna Magdalena. “Don’t cry for me, for I go where music is born”. Or so the first story goes. There is a romantic and emotional evocation about these words. One can almost imagine that music here should have a capital M. Though this unverifiable saying is touching, I find myself even more moved by what we do know to be true — Bach’s final work, which he did as he lay dying in his deathbed, was on a chorale prelude titled Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit. Before your throne I now appear.

That, I submit, is the worship woven with love and beauty that made Bach’s work ultimately authentic.